Dear members of Religions for Peace,

It is an honour to provide the enclosed copies of ‘The Voice of Hope: Aung San Suu Kyi from Prison – and a Letter to a Dictator’ to an esteemed organisation at the request of Aung San Suu Kyi’s son, Kim Aris. Published in early 2023, it is a distillation of the most significant insights in Burma’s Voices of Freedom, a four-volume set of interviews published at the end of 2020. Together, these works illuminate two profound injustices: the vilification of Aung San Suu Kyi in the media, and the unjust imprisonment of Burma’s elected civilian government by the military regime.

The interviews that became Burma’s Voices of Freedom, conducted by Alan Clements over the course of more than 30 months-long trips to Burma from 2013 to 2020, are documentary evidence of the thoughts, feelings and actions of dozens of leading figures in Burma’s decades-long struggle for democracy. These include National League for Democracy (NLD) leaders and co-founders like U Tin Oo and U Win Htein, as well as the late Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita, the architect of the NLD’s political philosophy of ‘national reconciliation’ and Clements’s preceptor when he was a Buddhist monk in Burma. Clements had privileged access to those at the heart of the NLD struggle through decades of close personal relationships.

There were several additional chapters that I compiled, like one composed from Aung San Suu Kyi’s speeches and presentations at institutions such as Yale University in the US and Sandhurst Military Academy in the UK, on key themes of her political philosophy. These were extracted from half a million words, much of which I transcribed myself, and presented alongside a 70,000-word chronology of key events written during those years, informed by Burma’s domestic news from sources like The Irrawaddy, Democratic Voice of Burma, Mizzima, and others.

The greatest part of my learning, however, came from transcribing and editing hundreds of hours of these interviews with activists, revolutionaries, journalists, religious leaders and politiciansover a period of five years. For five years, I lived with those voices. Every day, transcribing, cross-checking, learning. And I can say this clearly: in all that time, in all those interviews, not once did we find prejudice, racism, or hatred toward the Rohingya from Aung San Suu Kyi or the leaders of the National League for Democracy.

In fact, ‘Aung San Suu Kyi from Prison’ includes a lengthy section of statements and quotes of Aung San Suu Kyi’s which directly address the Rohingya crisis in Rakhine State in 2017. This is significant because Aung San Suu Kyi was near universally vilified in the western press as being “silent” on the plight of the Rohingya and “complicit” in the genocide perpetrated against them. The well-evidenced refutation of her so-called “silence” presented in this book was compelling enough that, in 2023, it was entered as a form of evidence in a case at a Federal Court in Argentina seeking universal jurisdiction over atrocities committed in Burma.

By that time, Suu Kyi’s reputation had been relentlessly tarnished. Years before her 2019 appearance at The Hague, the accusation of silence had been repeated so often that her complicity was seen as self-evident. In the mainstream international press, there were scores of articles critical of Aung San Suu Kyi, yet none about the actual perpetrator of the genocide against the Rohingya, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

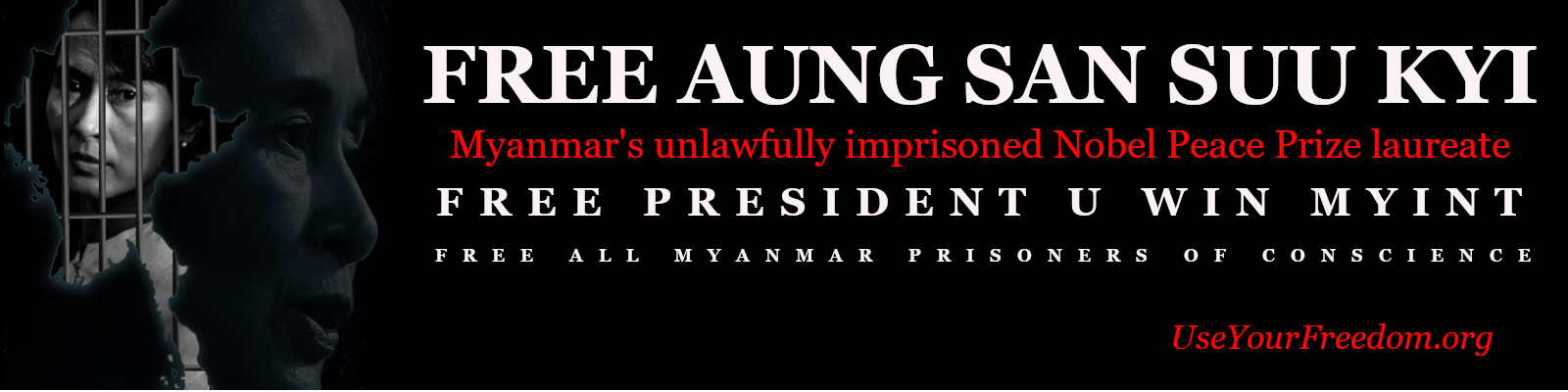

The irony, of course, is staggering. That a Nobel Peace Prize winning civilian leader of a nonviolent democratic movement is held incommunicado and in solitary confinement in an undisclosed location by the actual perpetrators of genocide - perpetrators who have not only escaped condemnation but who recently signed agreements with the UN for the repatriation of the Rohingya refugees they created - is a moral conundrum we have yet to fully grasp, never mind untangle.

Let me be clear: Aung San Suu Kyi was never silent. After communal violence broke out between Buddhists and Rohingya in Rakhine State in 2012, Aung San Suu Kyi spoke to the BBC, to VOA, to CNN-IBN. She issued statements, spoke up at press conferences, and called often for investigations into abuses. She publicly criticised the military for failing to dampen anti-Muslim sentiment and for their poor handling of the violence. She spoke about the need to protect ethnic rights in her very first speech in parliament, called the violence against the Rohingya a “huge international tragedy”, and when a new bill further limited Rohingya rights, she called it “criminal, discriminatory and in breach of human rights.” She met with numerous ethnic MPs and representatives of leading Muslim organisations, partnered with the Annan Foundation, and created and implemented a compressive economic plan for the redevelopment of Rakhine State.

While Aung San Suu Kyi was singled out by western media, she was not the only person that held the views she did. They were, in fact, quite common among the Burmese intelligentsia, and reported by outlets like The Irrawaddy. Radio Free Asia, Mizzima, Eurasia Review, Global Times and other reputable sources in Southeast Asia provided far more balance than the western press, and figures like Min Ko Naing, Ko Ko Gyi, U Win Tin and U Win Htein, as well as international observers like Dominik Stillhart, then-director of the Red Cross, and David Rudd, then-Prime Minister of Australia, corroborated her position.

While there who claim that what unfolded in Rakhine State in 2017 had nothing to do with a terror threat, Bertil Lintner and Iftekharul Bashar have been very useful in understanding the role of The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) in the conflict, as has the European Foundation for South Asian Studies. Similarly, those who persist in misrepresenting Aung San Suu Kyi’s intentions at The Hague persist also in misrepresenting her intentions in refusing the UN’s 2018 international fact-finding mission. However, the communal nature of the violence was something the UN, as well as the media, failed to accurately comprehend or describe. Crucially, the UN lacked any coherent strategy on inter-communal violence in Burma.

Even so, the 2018 independent fact-finding mission carried out by the UN did not find any evidence that Aung San Suu Kyi or her government had willingly or knowingly helped or enabled the military to carry out its attacks on the Rohingya. The US State Department report on atrocities carried out at the same time only mentions Aung San Suu Kyi in two paragraphs out of several hundred pages, providing only the barest biographical information in passing.

Yet the vilification of Aung San Suu Kyi in the press became pervasive from early 2015, when articles from out-of-touch observers like Mehdi Hasan, a renowned British journalist who is unlikely to have ever been to Burma, wrote an Al Jazeera article titled “Aung San Suu Kyi’s inexcusable silence.” His article appears to have been based only on the already published interviews with Aung San Suu Kyimentioned above rather than from any of his own sources. I repeatedly refer to this article because Hassan immediately contradicts his title bydescribing how Aung San Suu Kyi “shamefully blamed the violence on both sides.” These opposing faults of Aung San Suu Kyi’s cannot exist at the same time – either she was silent or she was not. And this was a time in which inter-communal violence had spread to three states, not just Rakhine.

There are earlier articles, like Guy Horton’s in the Ecologist in 2013, that read more like polemics based on rhetorical devices rather than information. Horton asks his readers, for instance,“Why is Aung San Suu Kyi condoning military atrocities by being present at Armed Forces Day?” a leading rhetorical question where the writer conflates hisinterpretation with fact. Aung San Suu Kyi was present because she was an elected MP negotiating a democratic transition, a negotiation that would have been harmed if she had snubbed the generals by being absent, not because she condoned atrocity. This was at the core of the principle of ‘national reconciliation’ she had been elected to carry out. Despite Horton concluding his article by listing his Cambridge University degrees and fellowships, ‘national reconciliation’ as a concept seems totally absent from his understanding.

Others have said that Aung San Suu Kyi “deliberately kept international eyes out of Rakhine State” by refusing the UN fact-finding mission, that she “denied the right to self-identify” by requesting diplomats refrain from the term “Rohingya.” But she partnered with the Annan Foundation to conduct a year-long investigation, inviting international eyes in, and used the term “Rakhine Muslim” because it was less inflammatory. But even this term is an implicit recognition of their inherent citizenship, something the Min Aung Hlaing denied when he refused to refer to the Rohingya as anything except ‘Bengalis’, or ‘foreigners’.

Behind the noise is a simple truth: if Aung San Suu Kyi had been complicit in genocide, journalists would not have had to say that she had been silent. They would have been able to find the words in which she was complicit in genocide. Hatred is hard to hide - there would bestatements like “there are no Rohingya in Burma” or that the Rohingya are“unfinished business from the Second World War” - both statements from Min Aung Hlaing. Consider that Aung San Suu Kyi spent her time as an MP calling for citizenship rights for the Rohingya “in line with international standards” and contrast this to some of the statements about Muslims in Gaza made more recently by ministers in Israel.

I believe the source of prejudice and misinformation in much of the reporting on Myanmar is not a partisan agenda or globalist conspiracy but the cumbersome complexity of a political process that was too dull, too dry, too taxing to offer excitement or relief, misinformation that shouldn’t be attributed to malice when incompetence is an adequate explanation. This incompetence in western reporting was shown, in research from organisations like CARE International and the Yusof Ishak Institute, to have exacerbated violence on-the-ground in Myanmar, to have increased nationalism, and to have pushed the people closer to the military.

Ultimately, this was an incompetence not born simply of the limited material resources like time and expertise common to the entire industry of journalism but tolimited moral resources. There was a lack of the moral clarity needed to understand that Burma’s ‘revolution of the spirit’, as Aung San Suu Kyi called it, was a revolution that began in the heart, with compassion, forgiveness, and the hope of redemption, even for the enemy. ‘National reconciliation’ meant reconciliation, and it meant reconciliation in a polarised world transfixed by retribution and the justness of violence.

I hope these copies of ‘Aung San Suu Kyi from Prison’ aid you in understanding Burma’s complex landscape and the fall of an icon for peace.

Yours faithfully,

Fergus Harlow