Myanmar’s nonviolent revolutionaries must not be forgotten

Democratic Voice of Burma, February 2, 2025

Peter Popham called her an Islamophobe. Bob Geldof, a handmaiden of genocide. George Monbiot wanted her stripped of her Nobel Peace prize.

But as Derek Tonkin observed in a 2024 Lowy Institute article, these critics—“inclined to zealotry and intolerance”—sought only to topple Aung San Suu Kyi from the pedestal on which they had put her.

In an open letter to Suu Kyi, Dzongar Kyentse Rinpoche writes that her persecution exposes a blatant double standard, that Burma must tell the truth about the colonial structures imposed upon it—structures that persist to this day.

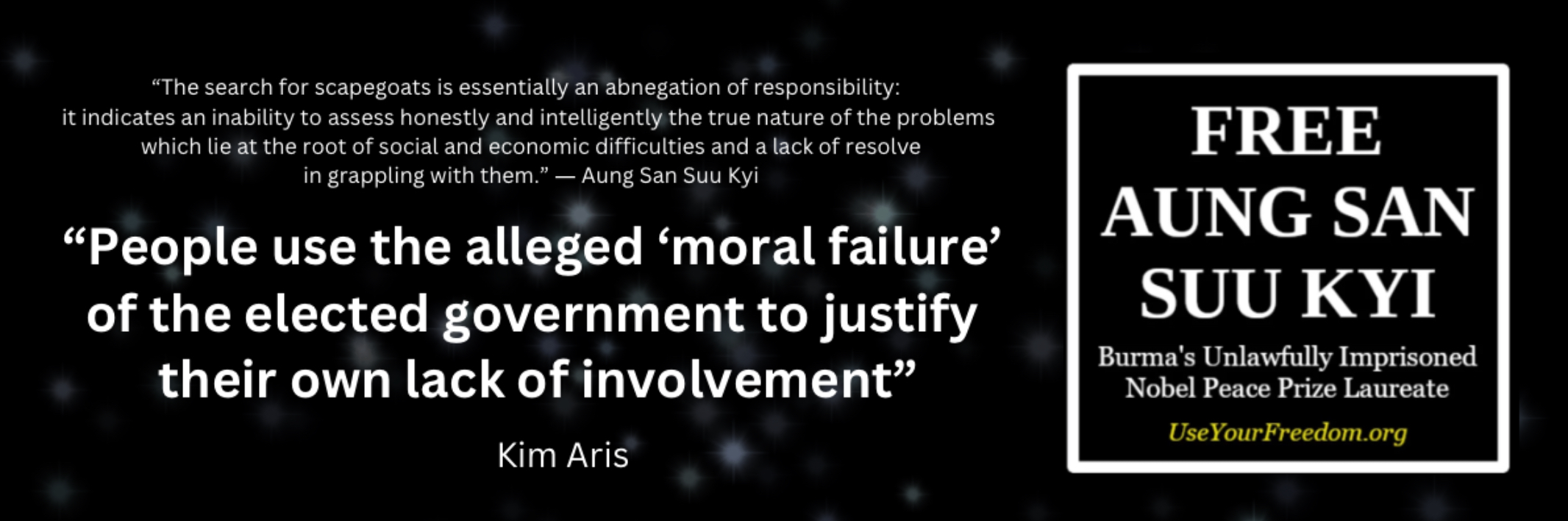

Aung San Suu Kyi’s youngest son, Kim Aris, remains an eerily lone voice in her defense.

Stripped of numerous awards, disowned by the West, and erased from the very history she shaped, Suu Kyi enters her fifth year of solitary confinement without an outcry—the silence of the international community a tacit endorsement of the junta’s cruelty.

By now well acquainted with conjecture, assumption, and half-truths, Kim tells me he has distrusted the media since his first interview at age 12.

“They turned it into Hallmark nonsense,” he says.

Kim Aris in conversation with Fergus Harlow

From 2012 onward, the international press worked assiduously to rewrite his mother’s legacy—casting her not as a hero of democracy but as a pariah complicit in genocide.

Yet today, Kim confides:

“Journalists I speak to now admit they got it wrong. They tell me their reporting was inaccurate—outright lies at times. But they say, ‘That’s in the past. We need to move on.’”

It’s one of several times I’ve spoken with Kim since co-authoring Aung San Suu Kyi from Prison with Alan Clements in 2023, a book containing thousands of words from Suu Kyi addressing the Rohingya crisis.

“Has this meticulous rebuttal to the accusations of her silence ever made it into your interviews?” I ask.

He scoffs.

“What I say often gets edited out.”

In 2017, The Guardian (UK) reported that Suu Kyi was under growing pressure to halt military clearance operations in Rakhine State.

But they failed to mention a crucial fact: Suu Kyi had no control over the military.

They refused to call the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) terrorists.

They didn’t bother to specify who was applying this so-called ‘pressure’.

I talk to Kim about how such manipulated narratives painted his mother as “the leader of Myanmar,” as BBC anchors so misleadingly called her, and how that distortion forever altered Burma’s future.

“The lack of response to the coup is directly tied to the Rohingya crisis,” he confirms.

A protester holds up a poster featuring Aung San Suu Kyi during a demonstration against the military coup in front of the Central Bank of Myanmar in Yangon on Feb. 15, 2021. (Credit: AFP)

“People use the alleged ‘moral failure’ of the elected government to justify their own lack of involvement.”

I ask Kim the biggest lie he has encountered in his short time in the media spotlight.

He doesn’t hesitate.

“That my mother is a nationalist or a racist—it’s simply absurd. Her government actively worked to end discrimination against the Rohingya, yet she was scapegoated for the crisis. People were led to believe that her party controlled what the military was doing.”

In the end, Kim points out:

“Neither the military nor ARSA wanted democracy to succeed. And the international community fell right into their trap.”

Aung San Suu Kyi is not the only one the world has abandoned.

Millions are displaced. Millions face starvation. Of 21,000 political prisoners, thousands have died in detention.

Kim tells me that the junta now uses the term ‘political prisoner’ arbitrarily—that many of those imprisoned are children.

History, then, may not look too kindly on coverage like Mehdi Hasan’s in Al Jazeera in 2015, which proclaimed:

“It isn’t Buddhists who have been confined to fetid camps where they are ‘slowly succumbing to starvation, despair, and disease.’ It isn’t Buddhists who have been victim to what… the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights has said could ‘amount to crimes against humanity.’”

But such divisive polemics have now become the lazy default of an increasingly myopic media landscape—a media that thrives on simplicity over complexity, outrage over nuance.

And as Burma descends further into civil war, seemingly to the perverse satisfaction of international observers, Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy are all but erased from history.

We are left with an uncomfortable question:

What moral duty does the international community have to a distant, war-torn nation it has so willingly abandoned?

As we approach the end of our conversation, Kim gives me a brutally unfiltered answer.

“Burma has become the global epicenter for human trafficking, organ harvesting, methamphetamine and opium production, cybercrime, and cyber slavery—horrors with far-reaching consequences across the globe.”

Then, his voice hardens.

“Calling for the release of these political prisoners isn’t just about Burma’s welfare. It’s about the safety of the entire world. It’s about our collective conscience.”

Because what happens when the world turns its back on those fighting for democracy?

It surrenders to tyranny.

And who among us is truly safe when tyranny is allowed to thrive?

The press may prefer the ‘new blood’—the fresh-faced activists untarnished by the weight of history.

But Burma’s future was built on the backs of those who suffered before them.

And as Kim reminds me:

“This resistance would not be where it is today without my mother and her party.”

“There was never any chance of moving forward without reconciliation.”

“Calling for the release of Burma’s elected leadership would be a powerful display of unity.”

Because to forget them now… would be to betray the very idea of democracy itself.

Fergus Harlow is a writer, scholar, and human rights advocate. He is the Director of the Global Campaign UseYourFreedom.org, which calls for the release of unlawfully imprisoned State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and all democratic leaders in Myanmar. He co-authored Burma’s Voices of Freedom and Aung San Suu Kyi From Prison and a Letter to a Dictator with Alan Clements, providing an in-depth exploration of Myanmar’s political crises and the resilience of its people.

DVB publishes a diversity of opinions that does not reflect DVB editorial policy. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our stories: editor.english@dvb.no