The Silencing of Aung San Suu Kyi: A Conversation with her son, Kim Aris

By Fergus Harlow, November 9th 2024

Please share

Kim Aris offers a powerful rebuttal to the international media's distorted portrayal of his mother, Aung San Suu Kyi, setting the record straight on Myanmar's complex system of government and the actions she took to reconcile a splintered country. In a compelling dialogue with investigative journalist Fergus Harlow, Aris reveals the misleading narratives that cast Suu Kyi as silent in the face of sectarian violence that reached a crescendo with the 2017 Rohingya crisis, and as complicit in the atrocities inflicted upon the Rohingya community by Myanmar's autonomous military regime.

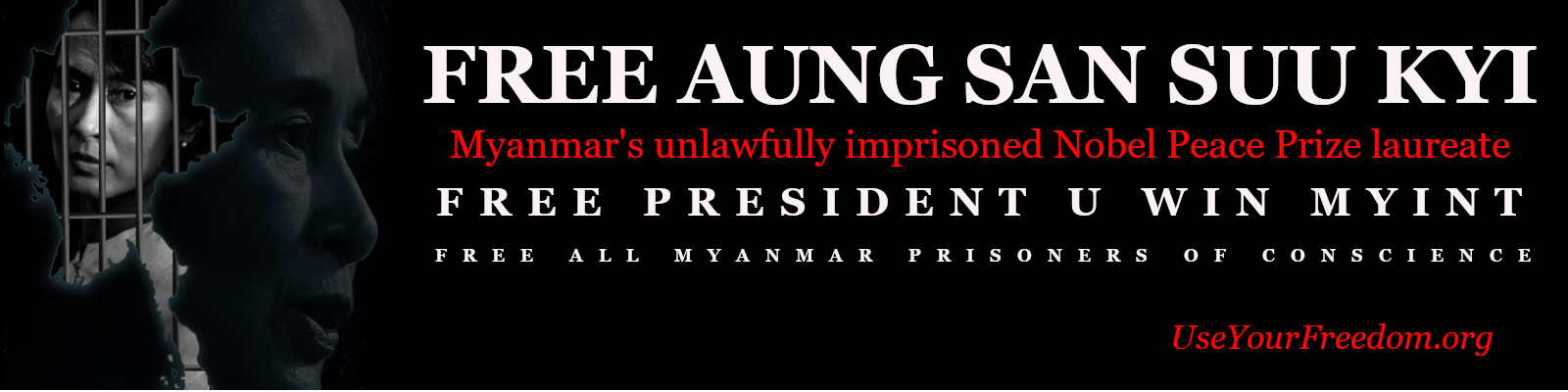

Emboldened by a narrative that ultimately allowed them to scapegoat Myanmar's civilian government while deflecting attention from their crimes, the military initiated a brutal coup d'etat in February 2021, detaining over 20,000 political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi and the country's other democratically elected leaders. Despite this humanitarian tragedy, voices speaking out for Myanmar's political prisoners are scarce, with inaccurate and insensitive reporting leading many to distanced themselves from the struggles of Myanmar's non-violent democratic movement. This conversation is an urgent call to reignite compassion and awareness for a nation in crisis.

FERGUS HARLOW: Kim, despite Pope Francis recently calling for the release of your mother, Aung San Suu Kyi, the silence from other world leaders about her politically motivated imprisonment has been deafening. Can you share anything about her current situation?

KIM ARIS: Heartbreakingly, there’s nothing to tell. No one has had any contact with her since January last year—not even her legal team. To be honest, I fear for her life. The situation in Burma is spiralling into deeper horror. My mother is 79 years old, her health is deteriorating, and the rumours of her being moved to house arrest are completely unverified. The last confirmed report we had was that she was in solitary confinement, locked away in a windowless cell under appalling conditions. Torture in Burmese prisons is common and has been well documented over decades, used as a political deterrent and, at times, even for sport. Out of the 21,000 political prisoners arrested since the coup in 2021, 2,000 have died. That includes 200 women and children. It's dire.

FH: Throughout her term in office, the media relentlessly criticized and condemned your mother for her response to the Rohingya crisis. It could be argued that the junta was emboldened by this widespread condemnation. Now, with the imprisonment of the democratically elected government after the military coup in 2021, the military junta has effectively decapitated democracy in Burma. Where do you find hope for your mother’s release?

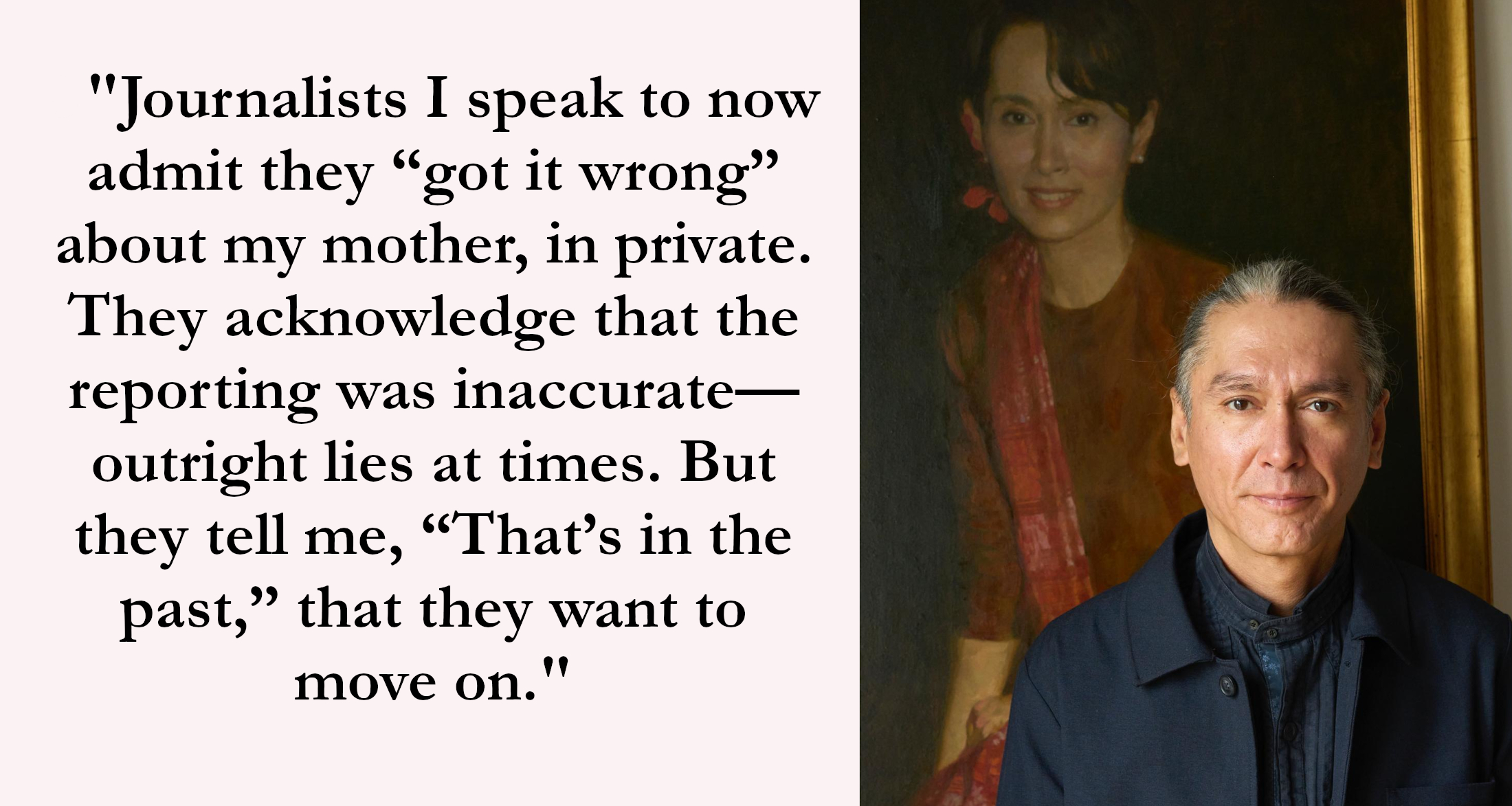

KA: It’s challenging, to say the least, and particularly hard that some journalists I speak to now admit they “got it wrong” about my mother, in private. They acknowledge that the reporting was inaccurate—outright lies at times. But they tell me, “That’s in the past,” that they want to move on. When I explain that my mother was never silent about the Rohingya, that she wasn’t complicit in ethnic cleansing, some media outlets seem interested, but what I say often gets edited out. I don’t believe Burma can simply “move on” from that.

"In reality, the military-drafted Constitution gave the military complete control. They didn’t have to report anything to my mother’s government."

FH: The international media has played a major role in distorting public perception. As the Rohingya crisis erupted in 2017, The Guardian (UK) reported that your mother was responsible for the military response in Rakhine State. The Associated Press and Al Jazeera published articles with damning misquotations, reporting that Aung San Suu Kyi blamed “illegal immigration’s spread of terrorism” and “a great rise in Muslim power” for the violence, neither of which she said. A BBC timeline of events falsely reports that only Muslims were arrested following sectarian riots, not Buddhists, though dozens of Buddhists were given prison terms up to 15 years, some with hard labour. What are some of the biggest untruths you've encountered in the media since that time?

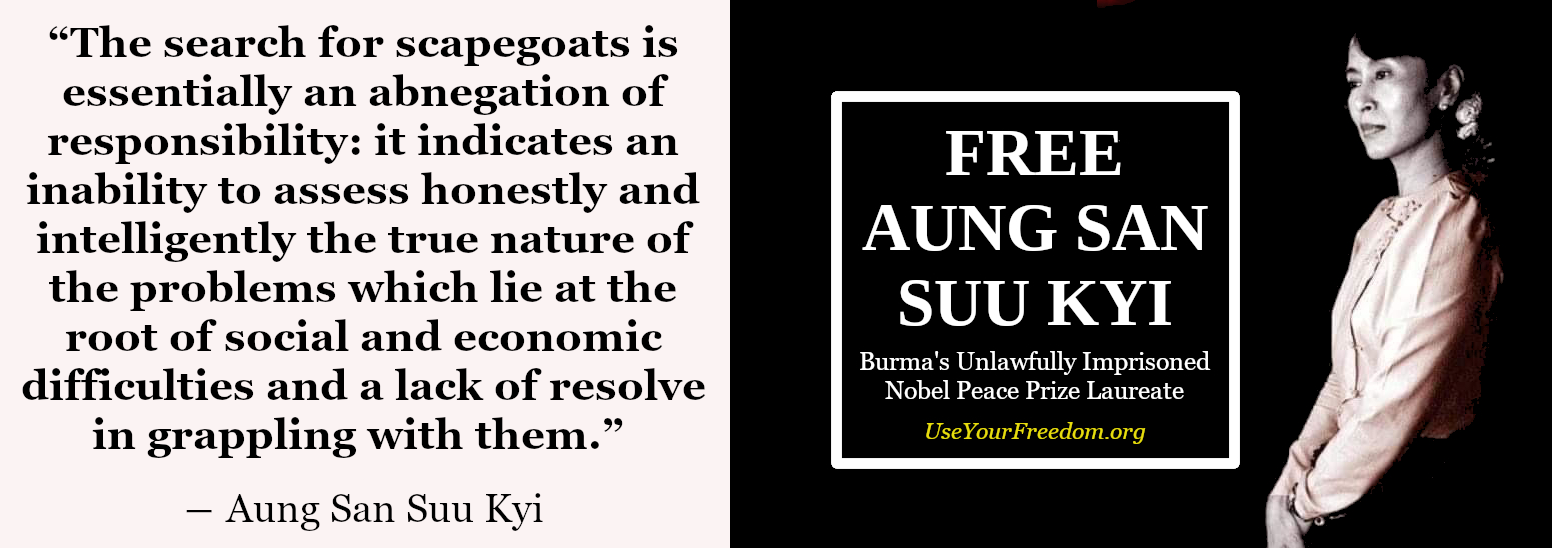

KA: Well, hearing what was being said about her at the time, I found it very confusing. It took time for me to work out what was going on, so it's not surprising that other people found it hard to understand. But the biggest lie is that my mother is a nationalist or a racist, which is simply absurd. She fought tirelessly for unity in a country fragmented by decades of military oppression, facilitated a historic agreement for democratic federalism between the various ethnic groups. She even commissioned a year-long investigation into the violence between Buddhist and Muslim communities, led by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Her government actively worked to rectify systemic discrimination against the Rohingya through civic and socio-economic reforms. But she was scapegoated for the Rohingya crisis. People were led to believe that her party controlled what the military was doing. In reality, the military-drafted Constitution gave the military complete control. They didn’t have to report anything to my mother’s government.

"Acts of diplomacy arising from the need to operate alongside an entrenched military regime were construed as complicity."

FH: One of the most glaring omissions is that of your mother’s policy of National Reconciliation. Acts of diplomacy arising from the need to operate alongside an entrenched military regime were construed as complicity. Yet National Reconciliation was a diplomatic imperative designed to allow the military to step back from power without inciting further conflict or animosity. Central to that approach, conceived of in partnership with the late Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita, one of the most eminent meditation masters of our time, was a dedication to overcoming division in Burma through a refusal to demonize or vilify “other”. Do you think she should have taken a harder line?

KA: There was never any realistic chance of moving forward without reconciliation, and that required compromise. My mother’s entire philosophy was built on the belief that dialogue and nonviolent resistance are the true paths to meaningful change. She understood that while war may be shorter, the healing process is far longer—and what we’re witnessing now was always a possibility she tried to prevent. While the military operated as an autonomous, parallel government, she wasn't letting them get away with their actions simply to make things easier for herself or her party. She beseeched the military and the police to intervene in inter-communal riots, but she had no control over them, and they took no action. She was constantly trying to keep the reins on the military, attempting to prevent exactly what we’re seeing unfold today.

FH: Having transcribed every available speech, lecture, and media appearance by Aung San Suu Kyi, having translations of every single campaign speech in Burmese from 2010 on, I saw no evidence of a nationalist agenda. When we compiled Aung San Suu Kyi’s actual responses to the Rohingya crisis in our book, Aung San Suu Kyi from Prison - And a Letter to a Dictator - many thousands of words - it moved a former UK ambassador to Southeast Asia, Derek Tonkin, to advocate for its inclusion in two international trials. One of those trials, brought against Aung San Suu Kyi by a rights group, has since been dismissed. What do you make of claims that your mother was “silent”, that she "fell from grace"?

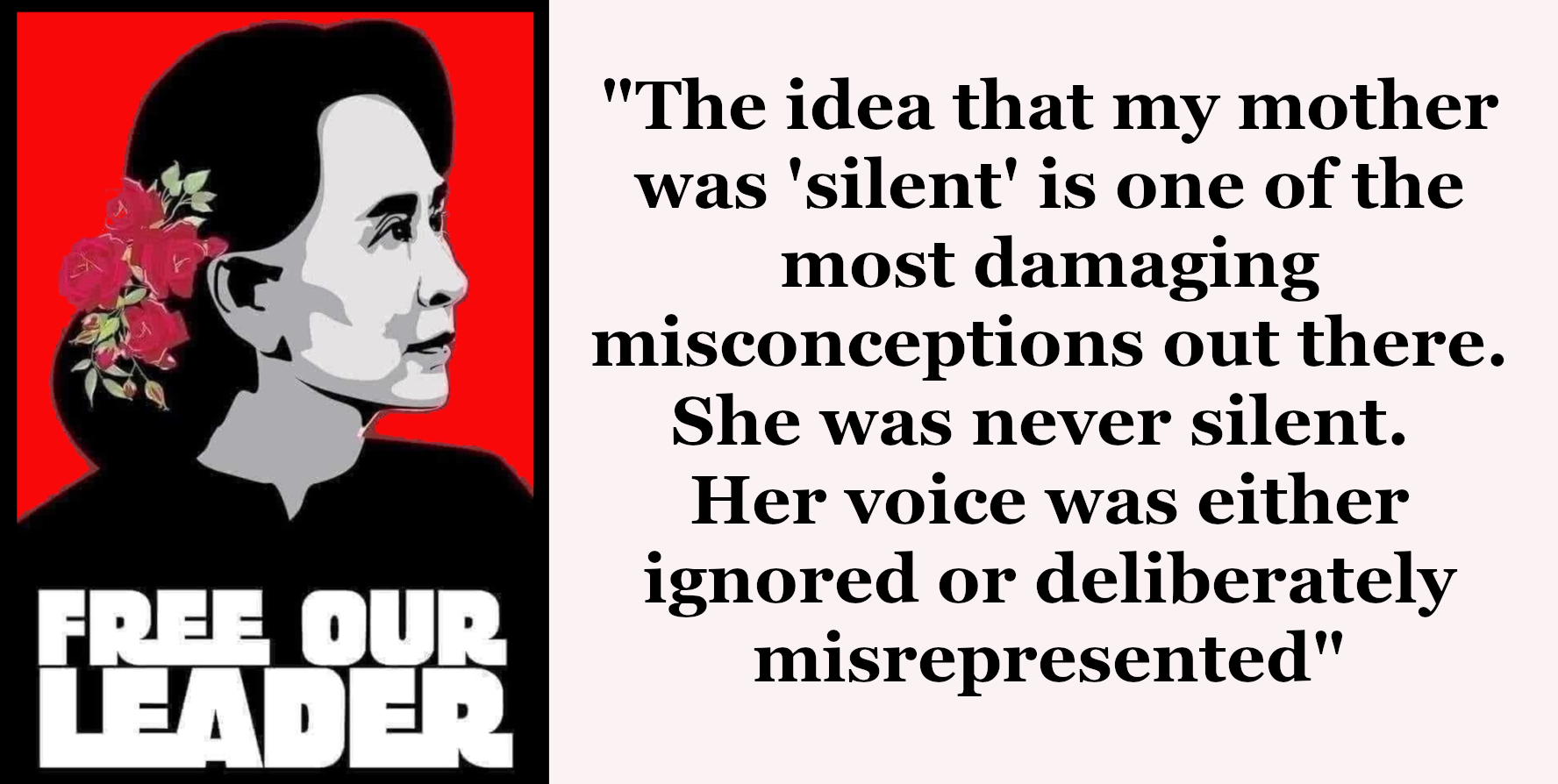

KA: Frankly, it’s as bad as calling Gandhi and Nelson Mandela terrorists, which is what the political establishment of their time did. The idea that my mother was “silent” is one of the most damaging misconceptions out there. She was never silent; her voice was either ignored or deliberately misrepresented. Her approach was nuanced—she was trying to hold the country together while working within impossible constraints. The narrative that she fell from grace is a result of people misunderstanding the extreme limitations she faced. Her goal was always reconciliation, not polarization. She knew that true progress required bringing everyone to the table, including those who were complicit in violence. To paint her as someone who simply stood by is both unfair and untrue. She was tirelessly trying to navigate a minefield, balancing international scrutiny, military resistance, and the desire for lasting peace in Burma. And she’s had death threats, and attempts on her life, over and over, and that’s never stopped her from doing what was right. That people believe that she's somehow flipped is unbelievable.

"ARSA’s involvement has been grossly oversimplified. They were portrayed as just another ethnic group fighting for independence when, in reality, they had no interest in Rohingya rights"

FH: Death threats were common throughout her term; her chief lawmaker, U Ko Ni, himself a Muslim from Rakhine State, was assassinated outside Yangon International Airport, grandchild in his arms, because he was close to finding a legal means of revoking the military Constitution. It's an assassination, traced right back to the military, that didn't make headlines outside of Burma. And having watched the huge amount of press that the Rohingya crisis received, the near blackout after the coup has been deeply troubling. Do you think the negative press your mother received has hindered justice in Burma?

KA: The lack of response to the coup is directly tied to the Rohingya crisis. People are using the alleged “moral failure” of the elected government to justify their own lack of involvement. But the blame should have always been directed at the military and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA)—the actual perpetrators. The reality is that she’s in prison while they remain unpunished. Worse still, they continue to kill with impunity. The fact is, there are now many more people in far more desperate situations, including countless Rohingya, and that’s exactly what my mother was trying to prevent through socio-economic reform and the rule of law. Now, with the economy failing in Rakhine State and with severe flooding, their are predications that these conditions will lead to mass starvation by 2025, with 2 million lives at risk. Muslim lives, Buddhist lives; no one there is safe.

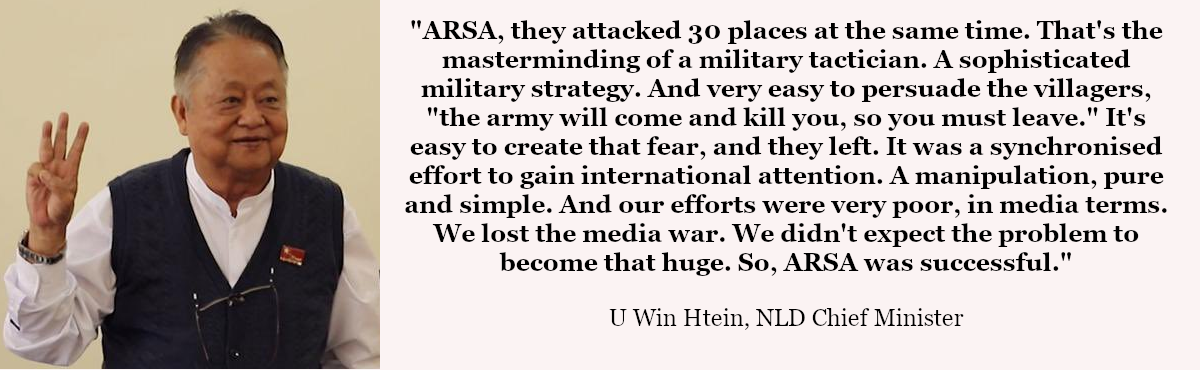

FH: It’s shocking that more people aren't aware of ARSA's role, or that the civilian government were being purposefully misinformed. The military had been facilitating inter-communal conflicts for years, and ARSA, through a simultaneous attack on 30 police and military posts, instigated an international incident that undermined the democracy movement. A jihadist group funded by the same networks as Al Qaeda, ARSA committed numerous atrocities against the Rohingya and other communities in pursuit of an Islamic State in Burma. Describing the attacks in 2017 as Burma’s October 7th Hamas event wouldn’t be inappropriate. Why do you think the international media focused on your mother and her civilian government?

KA: ARSA’s involvement has been grossly oversimplified. They were portrayed as just another ethnic group fighting for independence when, in reality, they had no interest in Rohingya rights. The media wouldn’t even label ARSA as “terrorists”, so people thought they were just another armed ethnic group. That was part of the inter-communal tension—with ARSA on one side, the military on the other, and the Rohingya caught in between. Neither the military nor ARSA truly wanted democracy to succeed, and the international community fell right into their trap. Even now, I hope that the Rohingya crisis is being used to draw attention to the brutality of the regime more broadly, but it seems only to divert attention from everything else. Until the international community recognizes these layers of complexity, real solutions will remain elusive.

FH: Alan Clements was on the ground in Meiktila in 2016, with U Win Htein, during riots between Buddhists and Muslims there, as well in the years following the Rohingya crisis. U Win Htein, who was your mother's closest advisor, spoke very movingly about the violence being inflicted on both sides, and described the tactics ARSA employed to derail the democracy effort. Evidence to us suggests the crisis was being used to distract from resource extraction and create the impression that only the military could maintain order. Burma is like Africa or Saudi Arabia in its wealth of resources. The black market jade industry, the narcotics trade, human trafficking—these are industries worth hundreds of billions annually in a country with a GDP of just over $60 billion. For some ethnic groups without international support, these illicit markets are their only sources of funding. Do you think the current vision of federalism could provide stability, a just economy, and align with what your mother was fighting for?

KA: Federalism has always been at the core of what my mother envisioned, and my grandfather, Aung San, as well—a Myanmar where every ethnic group has autonomy yet remains united under a democratic framework. They pursued this vision through democratic means, striving to change the constitution. Unity among the ethnic groups and democratic federalism might now be the only chance Burma has. When you think in terms of aid from the UN, for example, the UN fell short of its 2023 commitment by 60%, and by 85% in 2024. So where do people turn? But, now, we see the Arakan Army and other ethnic groups reasserting control over their regions, establishing systems of governance, healthcare, and education, while recognizing that unity against the junta is crucial.

"Calling for the release of these political prisoners isn't just about Burma's welfare, it's about the safety and welfare of the entire world. And it's about our collective conscience."

FH: So, would you say that your mother's political philosophy continues to be relevant to the current resistance?

KA: I think that even if the situation evolves differently moving forward, they would not be in their current position of strength without my mother and her party. Developments made during my mother's time in office have actually made the resistance stronger. My mother’s leadership laid the groundwork for this resilience. Calling for her release and involving the elected government in shaping the future of federalism would be a powerful symbol of unity among the ethnic groups—one that could inspire international support. I genuinely believe that for meaningful change to occur, the release of all political prisoners is essential.

FH: One of the military regime’s main tactics is to bomb villages and tea shops, indiscriminately killing civilians as revenge against the resistance forces. Do you think there now a threat of total genocide?

KA: Well, my mother was very careful about that word being bandied around, and it’s hard to bring it to bear in this context without muddying the waters. At the same time, what they’re doing is tantamount to genocide, one step away from it. When you think of the broader situation, out of a population of 56 million, 30 million are living in poverty, 20 million are in need of urgent humanitarian aid and relief, and there are three million internally displaced people. Those are huge figures. The military has the resources—missiles, jet power, drones—and no conscience whatsoever about using any of it, to create a situation of unimaginable horror. But people are not going to accept military rule going forwards, in any way, shape or form. There won't be a parallel government going forwards, because they've shown that they don't actually want to move things forwards for the country. It was just a pretence to try and remain in power.

FH: What might be the consequences for the international community if silence about the plight of Burma’s 20,000 political prisoners continues?

KA: When it comes to tangible impacts that people can relate to, Burma has become the global epicentre for human trafficking, organ harvesting, methamphetamine and opium production, cybercrime, and cyber slavery — horrors with far-reaching consequences across the globe. These issues resonate more with people than yet another distant humanitarian crisis. Calling for the release of these political prisoners isn't just about Burma's welfare; it's about the welfare and safety of the entire world, and about our collective conscience. These horrors are emanating from Burma, but we all share responsibility, and we all must take action.

FH: A final question, Kim; given President Trump's remarkable comeback in the recent US election, is there a significance for Burma in his victory over his own vilification at the hands of the media?

KA: President Trump's victory highlights a truth my mother knows profoundly: the power of the media to vilify and mislead. He has withstood a barrage of propaganda and personal attacks, and attempts on his life that echo the death threats my mother and her allies have endured. I hope Trump's commitment to open hearts and honest minds fosters peace and safeguards democracy, and I hope it shines a light on Burma's courageous freedom fighters on the global stage. I hope he can one day call my mother and her colleagues to the White House to discuss their insights on truth, justice, and reconciliation. I also hope he and his team will begin to call for the immediate release of the unjustly imprisoned leadership and recognise the urgency of their long struggle for democracy.

FH: It's clear from our conversation today that Myanmar's crisis goes far beyond what the headlines suggest. And it's not just about Burma's future, but about the survival of democracy itself.

KA: Exactly. This isn’t just a Burmese struggle; it's a fight for freedom, justice, and human dignity for all. The lies about my mother, the NLD, and the situation in Myanmar need to be exposed. The world must wake up before it's too late.

Republishing Rights Notice: